Una vez

más, las Malvinas en los medios. Y una vez más, el gobierno de la Argentina

sólo rechaza la opinión de los isleños, el discurso oficial del gobierno

británico o, si lo estima conveniente, la sociedad internacional y el orden

jurídico. El gobierno británico, a veces proactivo, a veces reactivo. Proactivo

en invitar a los isleños a toda negociación; reactivo, a cualquier declaración

que provenga del gobierno argentino.

Esta

vez, es el líder del Partido Laborista, el Sr. Jeremy Corbyn, quien

sorprendentemente pidió un "diálogo sensible" con la Argentina sobre

las Islas Malvinas controladas por los británicos.

Muchas

voces se han escuchado en menos de una semana. El siguiente párrafo las resume:

"Por

un lado, dijo que debemos entrar en discusiones razonables con Argentina sobre

su futuro. Por otro lado, dijo que los isleños tienen derecho a permanecer

allí, y tienen derecho a decidir sobre su propio futuro. Tomados

individualmente, éstas parecen proposiciones perfectamente razonables. Pero el

Sr. Corbyn claramente no tiene idea de cuan irreconciliables estos dos

conceptos están cuando se encuentran juntos.”

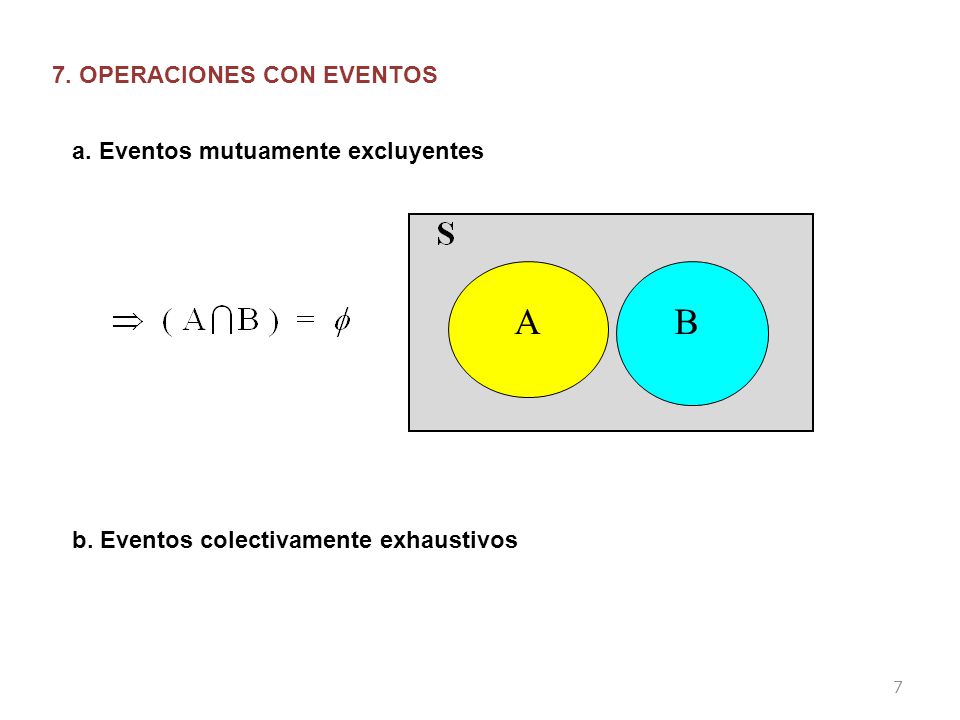

En

consecuencia, en lo que puede parecer ser un silogismo puro en la lógica, la

opinión general de lo que el Sr. Corbyn sugirió puede ser esbozada como sigue:

PREMISA

A: El Reino Unido debe entrar en discusiones razonables con Argentina sobre las

Malvinas.

PREMISA

B: Los isleños tienen derecho a permanecer allí y decidir su futuro.

PREMISA

C: Premisa A y B premisa son mutuamente excluyentes y colectivamente exhaustivas.

CONCLUSIÓN:

No hay solución posible para el enigma acerca de la soberanía sobre Malvinas/Falklands.

En consecuencia, el discurso del Sr. Jeremy Corbyn es erróneo.

No

estoy de acuerdo. Sin apoyar a partido político alguno, tengo que decir que el

Sr. Corbyn sólo afirma algo que en la teoría jurídica, la teoría política, las

ciencias políticas, la legislación es tanto posible cuanto alcanzable. Para los

que siguen mis escritos, saben que he estado trabajando en el caso Malvinas

durante más de una década. De hecho, varios de los mensajes publicados a través

de este blog demuestran el punto (por no citar artículos académicos en revistas

especializadas de derecho y ciencias políticas y otras contribuciones

académicas, participaciones, y discusiones en seminarios, congresos,

conferencias en todo el mundo).

El

conflicto, y más concretamente el conflicto soberano de Malvinas, no ha sido resuelto

todavía, tanto fáctica como jurídicamente. El lector puede estar de acuerdo o

en desacuerdo mediante un juicio de valor. Pero un juicio de valor no puede

estar en desacuerdo con los hechos y la ley. Las cosas son como son,

independientemente de lo que pensamos de ellas o cómo las valoramos.

Argentina,

el Reino Unido y las Islas Malvinas tienen que comprometerse si realmente

buscan poner un final pacífico y

definitivo a la disputa. ¿Qué implica comprometerse? En términos generales,

para comprometerse implica un acuerdo entre las diferentes partes en relación con

algo que ellos están reclamando y, en consecuencia, aceptar las reclamaciones

de las otras partes (o parte de ellas). Implica diálogo, y el diálogo implica

respeto mutuo, tolerancia.

Cierto.

Alguien podría argumentar que la soberanía implica un derecho exclusivo. Para

una definición clásica de la soberanía:

"[La

soberanía es] una autoridad suprema en un [E]stado. En cualquier [E]stado

soberanía recae en la institución, persona o cuerpo que tiene la última autoridad

para imponer la ley sobe todos los demás individuos en ese Estado y el poder de

alterar cualquier ley preexistente. [...] En el derecho internacional, es un

aspecto esencial de la soberanía que todos los [E]stados deben tener el control

supremo sobre sus asuntos internos [...] "

Martín,

E. A. y Derecho, J., ed. 2006. Un diccionario de la Ley. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Evidentemente,

hay muchas otras definiciones de soberanía que puedan proponerse. Por otra

parte, de hecho hay muchas cuestiones conceptuales que podemos considerar al

referirse a la soberanía del Estado. Se mencionan algunos de ellos a

continuación. El objetivo aquí es únicamente hacer evidente cómo un concepto

que al principio se piensa como absoluto presenta varias características que

muestran algo diferente. Algunas de estas cuestiones conceptuales incluyen:

· La

confusión entre autoridad suprema e ilimitada o absoluta y cómo los diferentes

tipos de límites-por ejemplo. internos, internacionales, religiosos se

relacionan con el concepto de soberanía.

· Si la

soberanía es una forma de autoridad o poder, o ambos.

· La

distinción relacionada entre soberanía de jure y la soberanía de facto.

· Si la

soberanía es una característica de una institución o de una persona o grupo de

personas. En relación con esto, la diferencia entre la soberanía como algo que

posee un Estado (por ejemplo, los Estados Unidos, Argentina) y la soberanía

como algo que puede o no puede ser poseído por una institución dentro de un

Estado (por ejemplo, la soberanía parlamentaria en el Reino Unido, la ausencia

de una sola institución soberana dentro de los Estados Unidos).

·

Estado con sobetrania "interna" y "externa."

· La

noción de soberanía "popular".

· Si

podemos pensar en la soberanía como algo poseído dentro de una jurisdicción

limitada (por ejemplo, "tengo autoridad sobre la materia X pero no sobre

cuestiones Y y Z, pero mi autoridad sobre X es final y completa, así que soy

soberano sobre X”) o si la soberanía debe conllevar una noción de competencia

jurisdiccional plena.

En

pocas palabras, la soberanía y la tolerancia pueden no aparecer como

conceptualmente aproximadas. Como la soberanía implica imperium absoluto o

autoridad suprema sobre un determinado territorio y su población (Estado soberano),

puede argüirse que posee una relación

antitética con la tolerancia. Sin embargo, el hecho que la soberanía puede -y de

hecho- tiene limitaciones refuta ese postulado.

Un

Estado soberano no es tolerante si no respeta a sus pares -i.e. si no respeta

la soberanía de los demás. ¿Respeta Argentina al Reino Unido en el caso de las

Malvinas y viceversa? En lo que se refiere específicamente a los conflictos de

soberanía, cada Estado soberano involucrado desaprueba las pretensiones del oponente

respecto al tercer territorio en disputa, y consecuentemente, implica un juego

de suma cero para todos los agentes implicados. Mediante la adición de la

tolerancia a la ecuación, estos Estados soberanos deberían al menos asegurar su

respeto recíproco como pares internacionales y, posiblemente, el reconocimiento

mutuo como agentes interesados en relación con el tercer territorio. ¿Hasta

dónde puede esta clase especial de la tolerancia internacional extenderse? La

respuesta a esta pregunta es crucial, ya que dependiendo de su resultado, la

tolerancia puede implicar el respeto de la situación actual (statu quo) en los

conflictos de soberanía o incluir comportamientos para avanzar hacia una

solución viable.

A

primera vista, la tolerancia parece ser generalmente entendida como implicancia

de obligaciones negativas -en la forma de no hacer, no interferir con otra

persona. Del mismo modo, a nivel internacional, el principio de no intervención

es fundamental para las relaciones internacionales.

Tanto

Argentina como el Reino Unido pueden actuar en relación con las Malvinas/Falklands,

conocen de su existencia y la de su competidor, y se abstienen de poner

plenamente sus derechos reclamados en acción. En efecto, existe un cierto grado

de tolerancia entre la Argentina y el Reino Unido. De hecho, el principal

problema entre ambos Estados soberanos es la disputa sobre la soberanía de las

Malvinas. ¿Puede un paraguas de la tolerancia ser la respuesta? Eso parece lo

que el Sr. Corbyn sugiere.

Un

primer -y maduro- paso para avanzar es que tanto los gobiernos de Argentina

cuanto el del Reino Unido acepten la existencia de su par en el conflicto, así

como a los isleños. En este blog ya hemos analizado porqué los isleños deben

ser incluidos en toda negociación y tener voz y voto. Ha llegado el momento de poner un punto final,

dejar de lado argumentos egoístas e infantiles, y avanzar hacia una solución

final, pacífica y definitiva.

La solución

que sugiere quien escribe estas líneas es la que cualquier persona interesada

en la paz y seguridad internacional sugeriría: Soberanía Compartida Egalitaria

que incluye a todas las partes, es decir Argentina, el Reino Unido y los isleños

de Malvinas/Falklands.

Algunos

posts anteriores sobre Malvinas/Falklands y soberanía: